Home » karate

Category Archives: karate

𝗨𝗦𝗦𝗥 𝗢𝗥 𝗪𝗛𝗘𝗥𝗘? – 𝗨𝗞𝗥𝗔𝗜𝗡𝗘 𝗪𝗔𝗥 𝟮𝟬𝟮𝟮

𝗘𝘅𝗶𝗹𝗲 𝗘𝗱𝘂𝗰𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝗢𝗽𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀: 𝗬𝗼𝘂𝘁𝗵 𝗤𝘂𝗮𝗻𝗱𝗮𝗿𝘆

During my stay in Lusaka, Zambia, 1975-88, some of my most memorable social interactions involved meeting older and veteran, mostly male South African freedom fighters. These were ANC members. Then in their mid-thirties and above, some of them had travelled the world. They would have been in pursuit of various goals, which included:

- Mobilization of international support for the South African liberation struggle efforts

- Military training

- Education

About all the veterans exhibited the abhorrent traits of arrogance, tribalism, bullying, cantankerousness, outright stupidity, and violence endemic of South African kassie/ township life. Hard partying involving huge consumptions of alcohol and drugs and all that it entails were an integral part of the deal. Needless to say. Shebeen culture carried with into exile. Not that Zambians were any less of party animals.

These veterans were people of all sorts, with all sorts of familial backgrounds. They, or we, as individuals or as special-interests sub-groups were motivated and threaded together by the collective higher dream of the attainment of the liberation of South Africa from Apartheid oppression.

Much as they loved to party by default, the majority of these people took their liberation struggle work very, very seriously. They were highly knowledgeable in the various fields of Social and Natural Sciences, including Mathematics. Some had had guerrilla operations experiences within South Africa in the 1960s; also, Mozambique and Zimbabwe in conjunction with fellow freedom fighters in those countries. Others had participated in major international wars, such as the Vietnam war, and in Latin America. These were hard people.

There were three distinct individuals with whom I shared intense mutual dislike for one another. Each in their own ways reminded me of some older guys and grown-up men that were generally not nice people back in my kassie, Thabong, Welkom. These horrible guys hated especially the ever vocal and visible little boys like myself then. It didn’t help my situation being son of an envied foreign man from Zambia. I had already been in Zambia for several years when I heard that, on separate occasions, five of the horrible guys got stabbed to death by younger boys on the streets. Good riddance. For the obnoxious people these men were, their souls deserve neither rest nor peace wherever they may be in after-deathland.

Regarding the three older exiles that didn’t like me very much in Lusaka, I imagine that a mortal confrontation would have ensued at some point had we been in South Africa then. The likely murdered wouldn’t have been me.

Zambia’s relatively laid-back culture had a way of dampening our wild South African township streaks. Otherwise, I got along fine with everyone; particularly those that found me “interesting to talk big struggle issues to”; their words, not mine.

My favourite was Comrade Mjaykes. He was Commander for a unit of younger, recently arrived immediate post-1976 Soweto student uprising exiles. Overriding objective here was to debrief the traumatized youth with various available and relevant medical and therapeutic methods. Intense and continuous conscientization political education was an unavoidable part of the package. And this was the fun part for me. Much of my fundamental geopolitics principles understanding was founded here.

Contrary to many a senior veteran, on the outset, Comrade Mjaykes was an unassuming personality. But he was one the most highly trained and educated around, both militarily and academically. He trained a lot, often alone late at night. He was very fit. And he read a lot too. Of his few personal possessions other than his books, he treasured a satellite radio that he had bought on one of his travels abroad. Commanding English, French, German, Russian, Spanish, and Swahili languages, the super veteran used the radio to listen to current affairs programs from all corners of the world. He was a well-informed man.

Being an exemplary leader with superior oratory skills, Comrade Mjaykes was a complete warrior in my eyes. An enduring source of inspiration that I last saw in 1981. Sadly, he was one of the earliest victims of the scourge of HIV/AIDS pandemic that began to ravage southern Africa and the rest of the world from the 1980s onwards. Comrade Mjaykes died in the newly liberated Rainbow Nation, South Africa, in December, 1994. No doubt, his soul is resting in eternal power. I can’t help but often wonder as to what he would have thought of the South Africa of today.

Acknowledging my Karate prowess already in 1977/ 78, Comrade Mjaykes said to me one day, “Much as I know you’d make a much better soldier than all these young comrades here, I’d rather you went to school first. You have the kind of brains there is a shortage of in our political leadership structures, see? We should be able to organize for you a scholarship for studies abroad. I’ll talk to your parents about this.”

“That would be nice, thank you! You know, my father’s biggest wish for my two siblings and I is that we could go and study overseas. But that’ll remain a pipedream because he could never afford the costs of an overseas education for us. Life is really hard for our family in Lusaka, as you know well.”

“Yes, I know! Your father is a good man. He deserves all the help we can afford him in that regard.”

“Thank you, Comrade! My parents would be extremely happy and grateful if mzabalazo/ the liberation movement can help.”

“It should work out for sure. But, unfortunately, currently available scholarships for full education up to university level are from Yuseserese/ the USSR (The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics). However, no, I don’t want you to go there even if you could leave tomorrow. My analysis of you and how you think tell me that you obviously are not Yuseserese material.”

“Why? How’s that? All I want is to be a doctor. A doctor is a doctor, no? There are Russian doctors at the UTH/ University Teaching Hospital, right?”

“Correct, a doctor is a doctor to the extent that he or she thinks only within the context of being a doctor and nothing else beyond.”

“I don’t understand!”

“Let me explain, Sae: you see, being a doctor, or any other modern, academically attained profession for that matter, is but just one of the multitudes of tools available for us to apply in the overall growth and development of society. You’ll, of course, recall that growth refers to the actual physical expansionary attributes of society; infrastructure, for example. Whereas development refers to the total conceptual and practical work that goes towards visualizing and realizing measurable qualitative and quantitative transformation of society.”

“Yes, growth or lack thereof is a function of ideas and tools constituting a society’s developmental visions as espoused by the incumbent national leadership.”

“Absolutely, Sae. Do remember that the developmental visions are promulgated in national development plans over specific time periods. Your brilliant explanation is further proof that sending you to Yuseserese will be a waste of what I see as one of the most promising of future leadership brains in our soon to be liberated South Africa. You must go to the West. Most of our smart ANC leaders in exile send their children to the West, anyway. There’s a good reason for that.”

In arguing his case, Comrade Mjaykes repeated a summary of standard rhetorical statements I had heard numerous times before:

- The Soviet Union is a Socialist state.

- Socialism is a transition state. Socialism puts together all the building blocks leading to Communism attainment.

- Socialism shall build a strong state designed to enhance optimal economic growth and protection of society and all that guarantees perpetuity of the imminent march to Communism.

- Communism is the highest state of existential wellbeing attainable for society. Under Communism, classes are non-existent; all are equal with equal access to all resources necessary and available for a life of non-ending abundance for all.

- The state machinery, i.e. bureaucracy, has the function of managing efficacy of Communism towards the full satisfaction of societal needs. Under Communism, given certain specific skills according to different levels of societal engineering and resources production and distribution administration, all are at the service of society first and foremost and last.

- Communism has no room for individualism, the basis for societal stratification, or classes creation. When Christianity and other religions talk about heaven, that’s another language for the perfect Communist state, actually. Only that Communism has no overbearing figures of God as portrayed in religious belief systems.

“That is the rosy picture of Communism, Sae. The reality is different. Just like the concept of heaven for the religious, Communism is utopian. The march to Communism starts and ends in the already dysfunctional Socialism, really.”

“But I thought that attainment of the Communist state was more realistic because it was based on the dialectical material world for material human beings without mythical angels and gods in even more farfetched heavens above somewhere in the distant sky.”

“Communism attainment would be more realistic had it not been for Socialism’s killing of the human spirit, Sae.”

“You are losing me now, Comrade Mjaykes!”

“I know that no one here has ever mentioned that last statement to you. I deliberately chose to prematurely take your political education to the next level now. That’s only because I really want the best for you and the future liberated, non-Communist South Africa.”

“If I may say so, you are beginning to sound like a sellout, Comrade Mjaykes. Aren’t you risking condemnation by others should they hear you talking like this to me now”

“No, my views in this regard are already known to even the highest levels of our command structures. My devotion to the struggle is known; I having been tested on many, many occasions over the years. But because we, the ANC, aren’t hard-core Socialists yet, there’ still much room allowed to hold principled divergent opinions in the on-going discourse of how to establish a unique, workable developmental model for the future South Africa.”

“I see!”

“And that is the point, Sae; behind the apparent success of Socialism in the USSR, North Korea, Cuba, and China, to name the most prominent, there are millions of robotized people whose senses of individuality have been broken to the core. Indeed, people may be provided with the best education in the natural and social sciences, producing top doctors, engineers, economists, and many more vocations. But that’s often as far as it goes.

That’s because, through various political indoctrination methods, backed by extremely brutal national security forces trained to think and act as robotically themselves, the ruling elite ensure that the people cease to think independently and critically over existential questions.”

“But I’ve thus far been made to believe that people in Russia and all these socialist places live happily ever after. Moreover, Russia’s support of ours and others’ anti-imperialist struggles were for that the world must unite against capitalism’s exploitative socio-economic relations subjecting us to lasting poverty and subjugation.”

“That’s a myth, Sae. The truth is that us South Africans we are just too free-spirited, too wild to tame for Socialism. It goes without saying that Communism isn’t even worth talking about. Our allied South African Communist Party is a good platform for training in polemics and rhetoric more than anything else. We’ll discuss higher level Capitalism issues another time.”

“I must say that this new side of Socialism has shocked me, Comrade Mjaykes.”

“You see, Socialism works for, and constructs linear thinkers; people who cannot think outside the box. People who think only in straight lines and right-angles in fixed operational spaces. Perhaps that may be one of the reasons Russians are superior chess players! I don’t know.”

It’s at about this time that my interest in chess waned. I dreaded the idea of my brains turning square! Indeed, many a South African liberation struggle veteran is a formidable chess player. If they ruled today’ South Africa as exceptionally as they mastered chess, the country would probably be in a better place. But political leadership is an infinitely open field presupposing capacity for paradigm specific, or beyond as necessary, multifaceted thinking in problem solving and application of solutions derived thereby.

“You have on many occasions demonstrated that you are a more independent and well-rounded thinker than your contemporaries here, Sae. I know that that’s why some of the older comrades here don’t favour you much. They simply hate your guts. Highly educated as they are also, these guys don’t take it kindly when they are pushed out of their intellectual comfort zones, especially by a young comrade like you. They are Soviet educated.

“I’d hate to see you stagnate or degenerate intellectually as you get older. That’s why you can’t go to Yuseserese for studies, Sae, you see? One or two young comrades of your calibre have died out there before. Some have had mental breakdowns. It would break my heart to see that happen to you. Although the truth is suppressed in our organization, racism is also rife in the USSR. Encountering racism out there is tantamount to jumping out of the South African Apartheid pan into the Soviet racism fire, if you ask me.”

At own private initiative elsewhere, the first scholarship chance I got for an overseas higher education was to Social Democratic capitalist Norway in 1988. I got stuck here. Primarily out of idealism and for love. No regrets. Norway is the richest country in the world. All things considered, life is as good as can be in Norway. Of course, never perfect, never fully satisfactory for everyone, but Norway does deliver for its people.

And the country is a leading Foreign Aid nation. Norwegian Finance Ministers have for years been megastars amongst their global colleagues. No Communism here. The few ardent Norwegian communists around are but fringe individuals or insignificant groupings with inconsequential social change impact, if any at all.

I write books now. I am what they call norsk forfatter. ‘Forfatter Simon Chilembo’ sounds ever so cool! I write without fear or favour, freely following my creative fantasies to wherever they take me. I live happily ever after in an effectively non-Communist state. If Comrade Mjaykes could see me now! All gratitude due.

USSR-Socialist trained South African national leaders across the board fail to get the Rainbow Nation out of the mess they’ve plunged it in after the fall of Apartheid in 1994. In big geopolitics questions, the USSR yoke is sitting comfortably on South Africa’s neck. Mzansi drowning with a sinking ship that is post-USSR Russia fo sho.

The USSR fall with the Berlin Wall in 1989 give rise to Russia. In essence, Russia is the ghost of the former USSR. Ghosts are no touch of reality. It’s therefore not surprising that, identical to South Africa contra Apartheid’s subsequent collapse five years later, Russia never could rise from the post Berlin Wall shambles. Oligarchs ruthlessly plundered the Russian state coffers, taking corruption to the next level.

Post-1994 South Africa created its own egregious oligarchic class through the State Capture phenomenon. This has shown many a Comrade from humble beginnings becoming millionaires to billionaires overnight. They have acutely incapacitated the South African state’s ability to optimally deliver the promise of a better life for all in a united, non-racial, non-sexist and democratic republic. The post-1994 South African oligarchic class has given the formally Apartheid state’s corruption colour. The former is living in the past. They have lost sight of the reality that Russia is not the USSR. Dismembering of the USSR is permanent.

In 2022, Russia invades Ukraine with chess moves mentality. Some things never change. It has turned out that Ukraine is not a chess board for Russia to play on as it wishes. Things have changed here. Parochial USSR legacy oblivious to this fact. Just for starters, young men of my age in the late 1970s are dying, falling like sacrificial chess pawns. The rest is a tragic war on a straight line trajectory ending potentially with a nuclear war catastrophe.

World in panic makes noise. USSR legacy ears are plugged. USSR marble eyes see imperial rebirth victory where the odds for survival are impossible to turn around. Meanwhile, Norway gives shelter and protection to Ukraine children and women running away from the ravages of Russia’s war on their country. No better place to be. Communism allergic. Progressive society as close to heavenly terrestrial opulence as can be.

SIMON CHILEMBO

OSLO

NORWAY

April 23, 2022

PS

The pandemic is still in our midst. Fears and factual untruths haven’t abated. In my 7th book, Covid-19 and I: Killing Conspiracy Theories, I highlight fallacies red lights and how to identify them. Order the book, read, and be inspired by my philosophical exposition on the matter. It might save yours and your loved ones’ lives.

DISCLAIMER: I neither offer nor suggest any cures or remedies. I promote fearless, independent thought and inclination towards pursuing science-based knowledge in times of, indeed, frightening, life-threatening phenomena in the world.

RECOMMENDATION: Do you want to start writing own blog or website? Try WordPress!

I REFUSE – A Poem

Fairytales in My World

Must I look away

From children

In my daily

Living spaces

On 2021 17 May

Norway’s National Day

Show-casing tangible

Children’s worth and joy

In a free world of peace

Whilst other children perish

At this very moment

In ravages of war

In baby Jesus’ world

Where peace is but

A concept in foreign vocabularies

Studied in Military Sciences

At Ivy League universities

Of this world

Jesus was a child of the wind

May be reason why

Nobody cares about

The fate of

Children of the soil

When the missiles rain out there

Must I obliterate myself

From the scene

The moment I hear

Children’s voices

In my proximity

Must I sing

I would rather go blind

Than to see

Children’s eyes on me

In their fields of vision

Fields of play

Must I be

Malignant angel

To a child

Warming my heart

With their purity of emotion

As I sense them

Must I suppress

My paternal instincts

To want to assure

A child that

I want only to

See them happy

Exuberant and free

Must I refrain from

Singing for a child

Dancing for them

Clowning for them

Reaching out

To touch them

For them to feel

The warmth

The honesty

Of my actions

My intentions

Must I ever look over my shoulders

In children’s presence

For fears

Of my actions

My intentions

Being misconstrued

By eyes

Seers of whom

For reasons obtaining

From their own fears

The nature of their lives’ journeys

Has taught them

To see only evil

In the acts of

The joyous

Glowing in the light

Of children

Yet to know

The sentiment of envy

The force of hate

I refuse

‘cause

I don’t know

How not to suffuse

Pure affection profusion

In view of children

I refuse

To succumb

To malicious fairy tales’ pitfalls by

Delusional prejudicial minds

Seeing reality

Through

Diabolic colours-tinted lenses

Tainting my honour

In view of confrontations with

Their own insecurities

In which their design

Their display

My hands

Never had a role to play

Could never want to

Never

Never

Never

On the contrary

My hands sought

Only

To build

Pillars of strength

Towers of power

Alas

In a moment of

Attention gone astray

Monsters were birthed …

(Continues in the book MACHONA POETRY: Rage and Slam in Tigersburg)

©Simon Chilembo 16/05-2021

SIMON CHILEMBO

OSLO

NORWAY

TEL.: +4792525032

May 30, 2021

RECOMMENDATION: Do you want to start writing own blog or website? Try WordPress!

PS

Order, read, and be inspired by my latest book, Covid-19 and I: Killing Conspiracy Theories.

THERAPEUTIC MASSAGE

PEAK PERFORMANCE TOOL

1986 shall remain an exceptionally memorable year for me. That is because:

- I finally became a university graduate with a cool BA degree in Humanities and Social Sciences. Then I went straight into a job in the Bank of Zambia (BOZ), a prestigious employer at that time. At relatively late-bloomer age twenty-six, I’d finally join the ranks of my contemporaries in Lusaka. Some of these had as much as an eight-year lead ahead of me as university graduates at various levels of further academic development, or as already practicing professionals in various fields.

What mattered to me at that stage was that I had also “finished school” and landed myself a great job. I envisioned that like everyone else I’d soon start making big money. Yes, I’d also begin to regularly travel to the UK and the USA on business trips. I’d buy myself a Mercedes, get hitched, build me a mansion, and make many children with my wives. Indeed, I’d maintain several mistresses with my numerous extra-marital affairs children too. Oh, yes, I had become a man, at last. Hallelujah! - I was at the height of my Karate training, competition, and leadership career in Zambia. At the same time, I was caught up in a mean power-struggle crisis with influential rivals in Lusaka. My crime was to ruffle feathers in conservative Zambian and Zimbabwean Karate establishments. Everybody loves a super star. But superstardom can create serious enemies as well; it comes with the territory.

- Perhaps during the previous year, 1985, a pioneering professional fitness centre was opened in Lusaka. What was then, by Lusaka standards, state-of-the art equipment in Slim-Trim Gym attracted the Health & Wellness conscious middle class in the capital city. Jane Fonda-inspired Aerobics classes were offered too, led by some of the most beautiful young women in town. I had to join the gym too, of course.

In no time I had become a well-paid Personal Trainer for several business executives and sports personalities, notably senior players of the Lotus Cricket Club of the time amongst them. I balanced the PT work and my own specialized fitness training needs as a national team athlete during lunch breaks; also during the hour between knocking-off at work and Karate teaching at the University of Zambia. I worked on weekends too. This was a very hectic schedule, to say the least. - During lunch hours over a period of several weeks I had noticed a former high-ranking Zambia National Defence Force officer making a nondescript entry into the gym and going straight into the Physiotherapy treatment section. He’d come out about sixty minutes later, and leave as quietly as he had come in. I used to notice that each time the senior officer came out of the Physiotherapy section, he seemed taller and more at peace with himself. He also walked with a more agile gait, just like it would be expected of a man of his vocation.

One day, during a pause between clients, Physiotherapist John caught me staring in amazement at the General as he was exiting the gym.

“Perhaps you are wondering why the big man comes here for treatment instead of the Army Hospital, Simon,” John said.

“He needs privacy, I guess. His juniors mustn’t know of his vulnerabilities, no?” I replied.

John, “You are right about the privacy need, yes. But the big man is not sick at all. In fact, he is in superbly robust health. He comes here as often as he can only to come and relax; to recharge the batteries, you see?”

Simon, “How is that?”

John, “Well, I give him Therapeutic Massage, which I learned in Holland. On the one hand, massage can be deeply relaxing during the treatment session. On the other hand, in the hours and days following the treatment, people become more energetic and resilient. This benefit of massage becomes more evident over time as people get more and more treatment. You might say that the big man is addicted to massage now. Actually, he often falls asleep during the treatments. He says this is the only place he gets to relax totally.”

Simon, “Oh, I see! I’ve often wondered what it is that goes on in there because he seems to take longer than anybody else.”

John, “Maybe you should try it too, Simon. You are a very hard-working man, which is good. But it’s not hard to see that you are very stressed. You know, massage can make you more dynamic in all aspects of your hectic life. You must try this!”

I then booked my first ever professional Therapeutic Massage treatment. It changed my life forever. By the time I left Zambia two years later, I was on top of my game all round. In 1996/ 7, my brother-from-another-mother, Saul Sowe introduced me to something he called Idrettsmassasje.

“That’s Sports Massage for you in Norwegian, Bro. As a Karate Master working as hard as you do, you must include Idrettsmassasje in your overall work routines. Come to my gym Trim-Tram, I give you some good massage and make you even stronger!”

Then my massage experience and journey went to another level. Such that, immensely fascinated by the power of it that I could personally bear witness to, I decided to good to school and study Terapeustisk-/ Klassiskmassaje, Therapeutic Massage formally. That was in year 2000. In relation to professional and personal development, including job satisfaction, my life took an exciting and enduring trajectory that has brought me much joy since.

Through the years I’ve met and worked with all kinds of people from all over the world. They’ve all had variable needs regarding their wellbeing as professionals, family members, and responsible value-adding members of society. It’s ever a thrill to look back and reflect on the thousands upon thousands of hours of my Massage work that have had lasting impact on people’s capacity and desire to work at Peak Performance levels.

It is scientifically verifiable that people shall be all-round high-level optimal performers when stress and bodily pains do not impede their ability to work with both mentally and physically demanding endeavours, regardless of duration. I’m myself a proud living proof of that. Therefore, it is with the highest confidence that I invite you to dare to make massage an integral part of your personal “Live for Success” package. Book your appointment with me as per contact information below.

Massage enhances your ability to ignite and radiate your inner power with confidence. Massage improves your posture and the way you carry yourself around. Investment of time and money on massage is an investment in your health. Investment in your health is the best investment you can ever make.

Simon Chilembo

Therapeutic Massage Specialist/ Terapi massasje spesialist

0253 Oslo

Telefon: +47 925 25 032

April 14, 2019

A TITAN IS GONE

REMEMBERING A WARRIOR GRANDMASTER:

JAMES BONAR NOBLE, SENSEI,

DECEASED August 11, 2018.

SPECIAL NOTES

- This is a very personal tribute. It’ll describe a special relationship that I had with Sensei Noble during the years 1978-88.

- I write with the kind of clear conscience that he taught me about. Furthermore, I write with the have-no-fear sense that he instilled in me. I write with the selfless attitude that he demonstrated in working with me individually, and as part of the broader Karate collective in Lusaka. That said,

- I write neither doing anybody a favour, nor expecting any favours from anybody. I write out of the sense of devotion he showered me with. The kind of devotion I have for, and have striven to show to my own Karate students, has been an attempt at replicating Sensei Noble’s Karate-Do spirit.

- I have not had any direct connection, at any level, with Sensei Noble since I left Zambia, in June 1988.

- Situations and events that are necessarily going to be mentioned in this piece are done so to the best extent my memory serves me. Any inaccuracies arising I apologize for in advance. Names of people mentioned are also done so with but only the best of intentions, and respect. If any inaccuracies arise here, or any insinuated malice is detected, they shall not have been intentional on my part. For that, I apologize in advance as well.

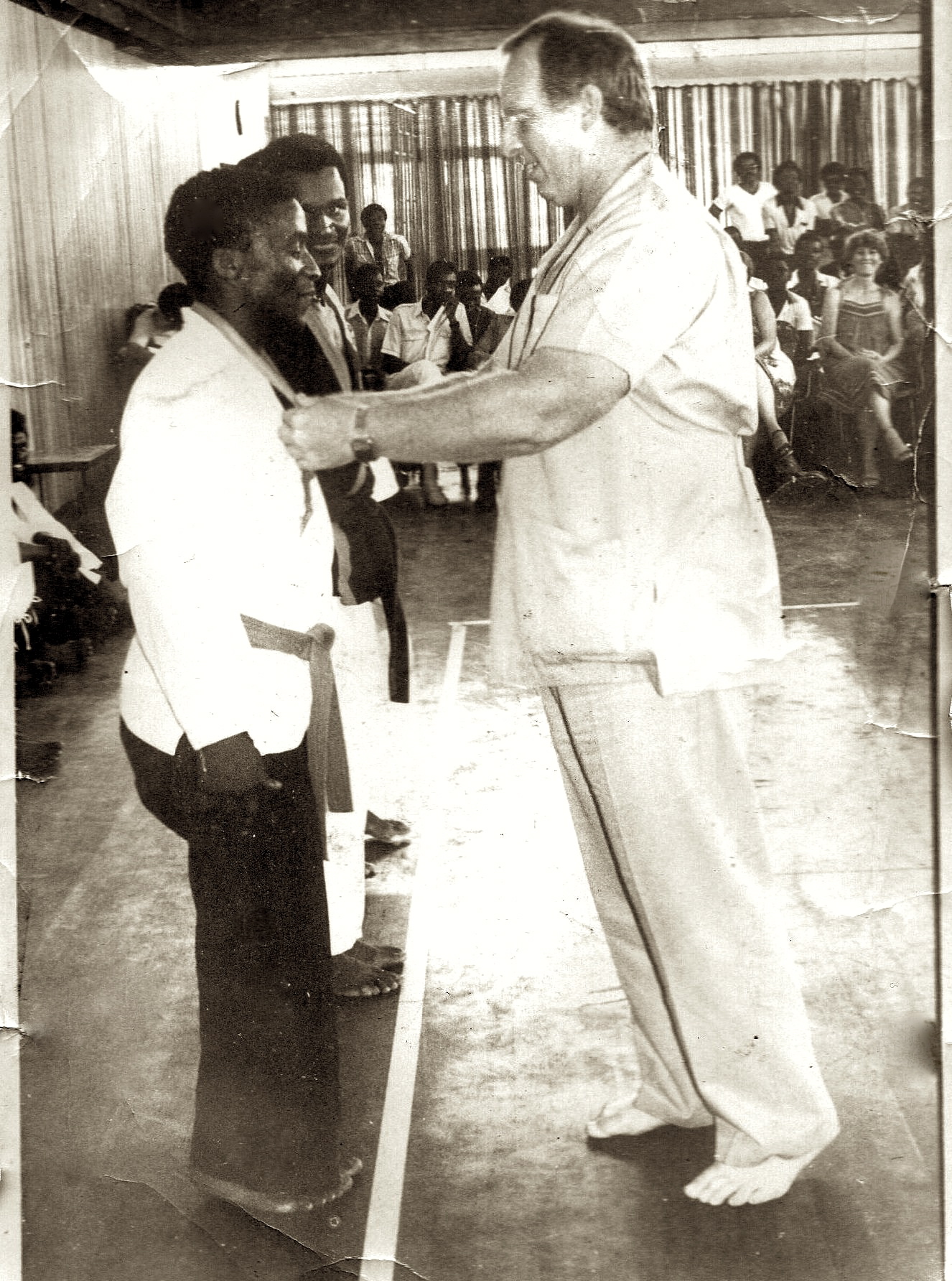

©Simon Chilembo, 2014. JB Noble, Sensei. Wycliffe Mushipi, Sensei, on my left. Presenting Zambian National Kata Champion Gold Medal, 1983. As I flawlessly executed the mid-air rotational flight in Kanku Dai Kata, in the dead still Nakatindi Hall, Lusaka, I thought, “How’s that for flying, Bonar? Your work!”

In 1986-88, my relationship with my fellow senior students of Sensei Stephen Chan is at rock bottom. We were the core group of the recently formed All Zambia Seidokan Karate Kobudo Renmei, headquartered at the University of Zambia (UNZA) Karate Club, in Lusaka. The issues were around mutual misunderstandings vis-à-vis organizational and club leadership roles. They were also around stylistic interpretations, and expressions of our new Karate style, Seidokan.

My biggest sin, though, was to decide to unilaterally take on Zimbabwean, Jimmy Mavenge, late, under my tutelage. I had trained the latter, and subsequently graded him to Sho (1st) Dan Black Belt in Seidokan Zambia Karate. The goal had been that he would, upon his return to his country, take Karate to the people, de-racializing the sport in the country in the process.

I was, inwardly, a devastated man during that time. One day, after briefing my mother about my difficulties with my Seidokan Zambia colleagues, she says, “Why don’t you leave these people, Buti? You cannot fight them alone; there is no need to. You can always form your own club, can’t you? Do that, for your own peace of mind, man!”

“Sure, ‘Ma, forming a new club is not a problem. But, you see, taking them individually, these people aren’t too much trouble, really; they are all driven by group power. However, I still have one person I think I can rely on. That is Sensei Noble. If I have him on my side, then, all these people can go to hell. However, should he side with them, then, I’ll quit.”

Jimmy Mavenge’s rebellious Black Belt grading took place during the middle of the second half of 1987, if I recall. The Seidokan Zambia Black Belts I had invited to witness the event weren’t, of course, willing to be part of the grading panel. That included Sensei Noble. They decided to take up positions on the mezzanine in the UNZA Sports Hall. So, I carried on solo.

In superb fitness state, his former guerrilla mutinous spirit tuned high, Jimmy ran through his gradings’ required routines like a possessed man. He passed with flying colours. Awarding him his diploma, I took my personal black belt off me and passed it onto him.

From the mezzanine, Sensei Noble exploded, throwing his arms up in the air in exasperation, “Did you see that? Did you see what he has just done? Now, it means we cannot annul this grading!”

Before he would turn and walk away, Sensei Nobles’ eyes and mine met ever so briefly. However, I didn’t see the intensity of negative emotion I had expected. His facial expression radiated a sense of wonder that I had seen many times at training with him before. At the same time, it was like he was saying, “Sorry, Semmy, but you are on your own now!”

And, I thought to myself, “Well, this is it, I’ve lost my trusted ally! But I ain’t quitting before my job is done. I owe it to Jimmy to help him make a smooth transition into Zimbabwe. And, I have to use the 1987/ 88 academic year to revamp the UNZA Karate Club (UKC).”

The club had almost collapsed following the squabbles of the senior Black Belts. At some point, only Jimmy and I would turn up for training. When he left for Zimbabwe, a few weeks after the gradings, I was left alone.

I do not recall if I ever did get to have a formal position in the then Zambia Karate Federation (ZKF) Board of Directors cabal. But I got to coach the Zambia Midlands Karate Team in 1986-88. That meant that, although the Zambia Seidokan deliberately excluded me from certain events, Sensei Noble and I would often meet in connection with our ZKF work. The Sensei was the active patron of the ZKF, then. In the ZKF domain, our relationship was as amicable as ever.

I shall take the writer’s prerogative and postulate that I have sat 10 000 miles with Sensei Noble in his car; all in ZKA related training and administration matters in Lusaka, and between Lusaka and Kitwe, in the Copperbelt Province. That would also include a trip to Harare, together with the Zambia National Karate Team, in 1981.

Sensei-Student bonding does not take place on the training floor. In the dojo, the Sensei and his students just want to kill each other, whilst, at the same time, the former’s job is to constantly remind the latter that “life is good, people. Love it, preserve it!”

Although I had no idea of it at that time, my Sensei-Student bonding with Sensei Noble took place in those 10 000 miles I’ve sat with him in his car.

“You have upset many people, Semmy. Stephen Chan Sensei is not happy with you at all. You have infringed upon Sensei Chiba’s territory. No good, no good at all, Semmy!” Sensei Noble said to me during one of our trips. This was sometime in early 1988, about six months after the Jimmy Mavenge gradings scandal. By then, I had already been to Harare to check on his progress.

I responded, “I’m well aware of that by now, Sensei. That withstanding, the work that Jimmy has already done since he got back home is amazing. It’s one of those occurrences that, to be believed, they have to be witnessed personally. I’m, now, even more convinced that we did the right thing.”

I went on to explain how Jimmy had started to train children and youth at Harare’s Mbare township, where the not so fortunate people lived. He had also started to teach Karate at an orphanage run by a close friend of his. All for free. On the other hand, Sensei Chiba ran a private dojo in the city centre, catering for the paying middle class, predominantly white. Efforts to reach out and pay a courtesy call to the senior Japanese sensei had been futile.

“Alright, Semmy Sensei, I will give you that one. But the others don’t know what you have just told me. We have to do something about this, then.”

I’m not quite sure now, but I have a vague recollection that, not long after I had left Zambia for Norway, Sensei Noble did drive out to Harare to check on Jimmy. On the trip, he had taken along one of my absolute meanest detractors. The rest is history.

While giving him the report on Jimmy, what I did not tell Sensei Noble was that my work with the former was, in a large measure, influenced by his off-the-mat teachings.

Sometime in the first half of 1979, tensions at our former Trinity Karate Club had become extreme. A point had been reached where either Sensei Noble or the bunch of new young lions Sensei had to go. If I recall, it was after the last training session that he would lead at the club, that he offered to drive me home to Chelston. The latter is nearly 20km on the opposite part of the city, in relation to his residence at the Andrews Motel, about the same distance away from the mentioned reference point

“You see, Semmy, everybody wants to lead. But people don’t realize that leadership is something you grow into. I’m really not sure if those guys are ready to lead the club. However, they want it, so they can have it. My conscience is clear, I have taught them only the best of Karate available in the country, if not all of Africa. If they now feel they know more than I do, fine by me. They’ll soon find out that real Karate is not found in books. Books guide. They don’t teach. Lasting knowledge is learned man-to-man,” Sensei Noble said.

He continued, “People don’t know that I have nothing to prove. I have no need to want to prove anything. Do these guys want me to break their bones to prove that I am stronger than them? Do they want me to jump and fly like a teenager to prove that I am a good Karateka? Rubbish, if you ask me!”

The Sensei was in his forties at this time.

©SIMON CHILEMBO, 2014. FLYING TO KATA CHAMPION GOLD MEDAL, 1983. AS I FLAWLESSLY EXECUTED THE MID-AIR ROTATIONAL FLIGHT IN KANKU DAI KATA, IN THE DEAD STILL NAKATINDI HALL, LUSAKA, I THOUGHT, “HOW’S THAT FOR FLYING, BONAR? YOUR WORK!”

With his left hand, pointing at his head, and tapping on his left side of the chest, Sensei Noble went on, “The point is, Semmy, I have it all in here. I can’t fly, and I have no desire to, so you know. But I can teach you how to fly. By the way, as from this coming Sunday, and subsequent ones, until further notice, I’ll be teaching special classes to interested Brown Belts and above. That’ll be at the Evelyn Hone College. We start at 9 o’clock. Feel free to join us.”

“Oh, thank you, Sensei, I’ll be there. Of course!”

“I know that public transport is a problem on Sundays. So, don’t worry, I’ll come and pick you up. And, do, please tell your parents that I’ll bring you back home safe afterwards, okay?”

“Yes, Sensei, thank you! You are very kind.”

“A sensei is like a father, Semmy. When you are good, he’ll be good to you. Always remember that!”

“Hoss, Sensei!”

One year later, Trinity Karate Club was in such leadership crisis that it had to close down.

Indeed, my work with Jimmy was a well thought out venture. I did it with love. I believed in the man and the cause he pursued, in that regard. My conscience was clear: I had no pecuniary, nor power interests; I was simply doing what my heart told me was right; I believed I had acquired sufficient knowledge to empower Jimmy to shake up the then racist Zimbabwean Karate establishment, and it worked; although I felt no need to prove it, I knew that I was strong and skilful enough to give anybody a good fight should the situation degenerate to that level. I would have been just too happy to break an enemy’s bone or two, actually. All this I had learnt from Sensei Noble’s way of Karate.

I do not recall how long the Sunday morning training sessions lasted, but it was many, many Sundays. True to his word, Sensei Noble would come and pick me up from, and take me back home. No complaints. No demands. Just training. I used to find it strange that this man, who also taught children at the Lusaka International School on Saturdays, did not take even a Sunday off in order to be with his own children and wife.

More than twenty years later, Martin Rice, a very special, Sensei Noble’s younger protégé from Ireland, is visiting us in Norway. Naturally, we begin to talk about our experiences with the legend. I mention the Sunday sessions, and the lengths to which our grand Sensei went to accommodate me.

“But, Simon, on those Sundays, after dropping you off at your home, he would, then, come home to me for another two hours of private lessons!”

Sensei Noble’s devotion to the Zambian Karate community that he raised single-handedly, at least in the Midlands, up until the 1980s, has made a lasting impression on me. That he even had the extra capacity to work with the select few of us in the manner that he did touches the softest of my emotions to this day.

There has been a time I asked Sensei about his level of engagement in Karate. He replied, “Well, Semmy, funny that you should ask. You know, once the spirit of Karate gets into you, it consumes you. But, each time you see the good things Karate does for people, and, by extension, society, you can’t stop it. You can’t live Karate half way. You can’t teach Karate halfway. People will come and go. But you have to be there all the time. One day, a student of your calibre, Semmy, walks into the dojo, and you, then, know that there is no way you can let this talent down. And, so, you just give and give. It’s such a joy, Semmy. My family understands that Karate is an important part of my life.”

Back in Zimbabwe on a normal civil servant’s salary, Jimmy no longer had the kind of cash he used to have whilst on his diplomatic tour of duty in Lusaka. He couldn’t afford to pay for my visits to him. I visited him twice during the first half of 1988.

In his humorous way, Jimmy had a brilliant idea, “Shamwari Sensei, you mean after all these years together you haven’t learnt even just a bit of diplomacy from me? Soften yourself, be nice, go down on your knees and ask the Seidokan Zambia people to sponsor your trips here. We have already crossed the Zambezi, anyway, and Seidokan Zimbabwe is here to stay. So, they better work together with us now!”

I had already started to make my own money then, “No, no, no, Shamwari Sempai, Senseis sponsor themselves and their students, you see!”

Through working with Sensei Noble, I learned that a Sensei must be self-sufficient. A Sensei that depends on sponsorships and donations cannot do his work effectively.

On a drive from Kitwe to Lusaka, Sensei Noble is cruising at between 140-150km/ hr. A Mercedes Benz overtakes us like it was a bullet, and soon disappears from our sight up ahead. Perhaps 15 minutes later, we approach a road accident spot. The Merc had overturned. It had rolled several times, apparently. Totally wrecked.

“Yes, that’s what you get when you drive at a speed like that on roads like these, Semmy. Karate teaches us to always be aware of our surroundings in relation to the actions we wish to undertake. From that, we can calculate and predict likely outcomes. I knew that that car wouldn’t reach Lusaka, driving at that speed,” Sensei Noble spoke wryly as he drove past the accident scene. We would learn later that the driver of the Merc had died on the spot.

The grand Sensei has told me that when he first came to Zambia in the early 1950s, he had only the amount of pocket money a fresh university graduate from Scotland would have in those days. Not much. He landed somewhere in northern Zambia, somewhere around Lake Bangweulu, if I’m not mistaken. To pay for his hotel stay there, he offered to hunt game for the establishment. That’s how he started off in Zambia, a place he had come to with no intentions of living in permanently.

From that experience, he has said something like, “You see, Semmy, as you get older, and you start travelling the world, you’ll soon discover that there is more to you than who you think you are: your race, status, education, and the like. You’ll find that you get to places where none of that counts. So, in order to survive, you have to look for solutions in things that you never even knew about before. That’s how a Karate man’s mind works. Just like people fight differently, you can beat anybody with the same techniques, but adapting them to the kind of man attacking you. That’s how life is, the essence of you does not change, but your attitudes can, and have to, according to where you are, and the circumstances you find yourself in.”

I applied that Sensei Noble’s philosophy in Norway. Whilst in a place I was not supposed to be, for an act I was not supposed to commit, a colleague saw through me, “You Simon, I know your type. You are a survivor. Don’t tell me that you are a Massage Therapist because that’s a career path you had planned all along. I know you are good at what you do, but you chose to study Massage Therapy out of survival pragmatism needs, given your life circumstances in Norway. You are cut out for greater things, and I know you know that!”

Yes, Sir, I do. But until the greater things come my way, I’ll do what I gotta do to survive here and now, as per my Sensei Noble’s teachings.

Whilst in Harare with the 8-man Zambian National Karate Team, in 1981, I was singled out to join Sensei Noble as he joined two other Zimbabwean senior Black belts (whites) to tea at the home of a Japanese diplomat. I do not remember the name of the diplomat. Present were also the dreaded Sensei Chiba, and two other Japanese Judo Sensei. I was a not so sophisticated, little 20 year old schoolboy, then. But the grown up, senior Budo masters were real nice to me. I recall Sensei Chiba advising me to use whatever nature provides to train with, if I cannot go to the gym. “If you do not have a punch bag, there is always a tree to punch!” he said.

Driving back to our hotel, Sensei Noble said, “You were highly honoured today, Semmy. High-ranking Japanese don’t just invite any strangers into their homes.”

“Hoss, Sensei!” was all I could say.

An aspect that is not spoken much about is that, in his pioneering work of opening up possibilities and teaching black Zambians Karate from the late 1960s, Sensei Noble was, actually, treading on thin ice. That’s because, in my view, that was a time of numerous state coup d’états across the African tropics countries. White mercenaries, whom the media romanticised as Martial Arts experts, led many of these coups. “Mad Mike” Hoare is the first name that comes to mind here. A reliable source has disclosed to me that there were concerns that some of Sensei Noble’s Karate students could be enticed to join the lucrative (for those who don’t die!) mercenary bandwagon. So, relevant Zambian State Security organs closely watched him, and the whole lot of his prominent senior students.

I am sure that there are many others in the Zambian Karate fraternity who’d concur with me that Sensei James Bonar Noble gave us, individuals, and the collective much more than we could ever ask for. He, like other ordinary mortals, was not perfect. I, for one, am not in a position to cast any stones. Unfortunately, by the time the roses in my garden bloom in the spring, I’ll have relocated to another abode.

My heart felt condolences to the Noble family in Lusaka. The same applies to the Zambian Karate fraternity, if not the nation, for the coming to an end of a life of an illustrious service to the people through the Martial Arts. Many of Sensei Noble’s students and their own protégés continue to tread upon the selfless path of humility, giving, and devotion that he started. Their impact is felt across the cross-section of the Zambian society. Some are also forces to reckon with in various parts of the world.

Sensei James Bonar Noble may be gone, but he shall never be forgotten. His legacy is just too deeply engrained in the psyches of many of us. May his soul rest in eternal peace!

Simon Chilembo

Welkom

South Africa

Telephone: +4792525032

August 13, 2018